I am a lover of odd numbers. That sentence — in words and syllables — is odd. But not intentionally. Intent is important, which is why I wouldn’t use the word compulsive if I ever needed to explain the 5 miles at the gym, the 7.3 gallons of gas, the 15 lines of notes I write in each of my patients’ charts. I will go out of my way to get an odd but not so much that the pursuit radically alters the course my day, which is why I wouldn’t use the word obsessive either. I’d rather describe these odds — my odds — the same way I’d describe my bod. Quirky. Not unhealthy. Hairy.

I blame my odds for unfairly priming me for 2017. It was not our forthcoming first female president (a sure win) or the fact that I was graduating with my professional doctorate as student body president (a win I will explain later). I was psyched for ’17 only because it was a shiny odd: dancing queen, seventh prime number, sum of a haiku. The constituent events of the year did not cross my mind. By a definition of my own design, ’17 was destined to be lucky, couldn’t and wouldn’t do me wrong.

The night after my 26th birthday, well-fed on my reckless certainty, I slept soundly during the election. I woke to a nightmare, saw that the coming year was getting even with me fast, and — rightfully — panicked.

So began a year of sudden deaths, a year that wasted no time. Just hours after New Year’s, ’17 took my grandmother from me. Teta lived in Lebanon, and none of us — including her shattered daughter, now changed forever — got to say goodbye. The pain of that loss both invalidated and intensified all the other pain we’d feel that year. Her death tinged my graduation with numbing futility (my DMD, my pursuit of ‘creating smiles,’ sounded so moronic to me during my final semester that I repeatedly considered going back for an MD to treat diabetics like Teta, only to acknowledge — repeatedly — that it was too little, too late). Her death gave the xenophobic actions of our new administration an intensely cruel, personal sting (what if she had lived? needed to come here for an operation? and couldn’t, because of them?). Nothing existed without her context, so ’17 became both the year she’d leave us and the year she’d left us with.

My odds had never failed me before ’17. I mean, I’m sure they must have in small, unnoticeable ways, a fact I can admit now with some humility. But this is not so much an essay about odd numbers as it is about luck — luck as a facet of culture, as a language. What luck says and what it does — or can do — to us. And why.

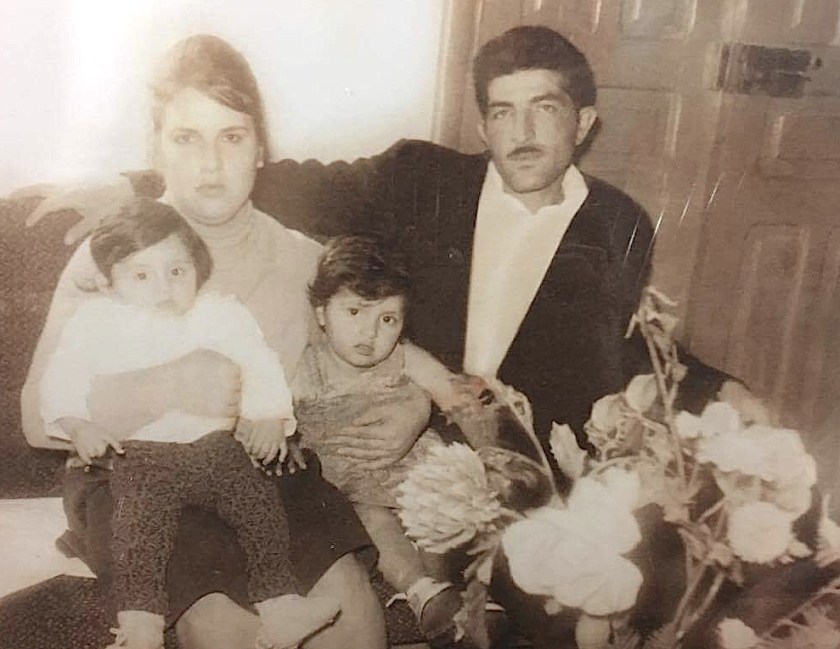

Before her death, my grandmother lived on both ends of the luck spectrum. In her prime, Teta was a stunner, fair-skinned diva of the 60s and 70s. She still peers out of old photographs with a defined cupid’s bow, hazel curls, and a serene but intensely concentrated gaze. Even in sepia, she is vibrant enough to snap a neck. Not a single carpenter who worked for my grandfather didn’t openly gawk at her at some point or another, gazes she would coyly record and softly mock in the men’s absence. She was rich, too; my grandfather was the wealthiest man in his district. My mother remembers him bringing home suitcases full of colorful, tightly bound banknotes.

It was said that Teta took after her mother — my great grandmother — a woman whose beauty inspired fear. She was killed in a jealous rage by another woman. After, Teta was shuttled around, raised at the abusive hands of relatives who chose to remember her mother as unwholesome, taboo. Because they were feeding her, she became their little slave. She cleaned, cooked, and looked after her uncle’s children. She wasn’t permitted to finish school. She married young — like some girls do, often by uninformed choice — to escape.

Teta was smart. Her social intelligence — her perceptiveness, sharp humor — rivaled her beauty. Many of her jokes were puns or plays on sounds, double meanings. I remember ignorantly reasoning, “Well of course she doesn’t read in English if she can’t speak it,” too American to realize that she didn’t read anything, Arabic or English or otherwise. The fact that this was solely due to her upbringing upset me as a child and continues to enrage me as a woman. By some fortune, some women in Teta’s era got to go to school. Others simply did not — this latter lot never getting to experience the private high of a good book. Never permitted the thrill and clarity writing provides, how it can feel like a second home. Not the home you are born into but one you create — in a hodgepodges of tastes that change and layer with your age and education — all on your own, populated with characters that never die.

She could, however, read coffee. My mother, my aunts, and Teta would spend bright mornings together in the garden, a shiny, full raqwa and several cups between them. When they were finished drinking, Teta flipped the cups over their saucers, swirled them, and waited for them to dry up. Then she would read the resulting patterns in the grounds that clung on the insides of the porcelain. Here was a fish with a big mouth — a piece of fortune, money. Here was a gathering of people — an award. Here was a perfect round band — an engagement! Here was a white paper floating — good news. Here were several candles in a line — wishes come true. And of course, the much sought-after, stunning white horse — a groom!

Teta let me sip coffee with her and my aunts for the first time when I was nine. I remember how much I admired the mini cup, its glazed brushstroke patterns and smooth texture. So easy to hold. It was too bitter to finish, so she tossed the rest of it in the red earth of the garden, flipped my cup, and read it for me. All good fortunes! A future as bright as that morning! To this day, I still take my coffee black.

In 2000, while we packed for our trip to Lebanon, I stuffed my backpack with so many novels and notebooks that I had to drag it through airport security (I was a scrawny kid). I kept a journal for day-to-day adventures. In the humid evenings, after the electricity fizzled out, white stars and mosquitos appeared simultaneously. I’d remove my notebook and start scribbling in the blackness, swatting my sticky thighs until they were red. Every day for three months in the summer of 2000, I opened with the words “Dear Journal, it’s me again” as if anyone else ever wrote there.

On one of those days, my uncle handed Teta a paper to sign. She’d just fried us fresh eggs for breakfast. Suddenly, the deft hands that had split fragile shells and flipped the hot and heavy pan left her. She held the pen with a childlike, craned grip. Her movements were focused, abrupt but careful — the way you hold a baby or a wriggling puppy for the first time. For a few seconds, she wasn’t the same animated storyteller who found white horses in black coffee.

In 12 years, she would hold all objects like that — with flattened, seemingly webbed fingers. Not because she was trying to trace the alien letters of her name from memory, but because diabetic polyneuropathy had eaten through her peripheral nerves. Her mitten-like motions, tiny as they were, weakened me; more than than her failing memory or eyesight, her budding periodontal disease, her inability to walk. Her fingers cut my heart worse than any of her comorbidities.

We flew across the Atlantic about every five years to see my grandparents in Lebanon, but Teta only visited us in Ohio once. She instantly hated it. She came during the icy September of ’03, a few months before my little brother was born. My sisters and I were too young and too stupid to converse with her meaningfully, much less marvel at her as a living relic of the past. The flat Midwestern horizon strained her eyes, as did the straight and narrow walkways, the cool buzzing streetlights, the near-identical suburban homes lined up as if on death row. No one used wood to construct homes in Lebanon (too temporary, too flimsy – besides, chopping cedars is illegal business), and when we creaked across the living room or hallway, she couldn’t help but turn stiffly to the source. How did people live here? I was made more aware of her unease when I’d look up from my book and catch her at the window facing the street, frantically and quietly worried about my pregnant mother driving to her college night classes. She left shortly after she arrived.

I was mad at her for it. I was 12, had an American superiority complex paired with an egotistic, tween brain. She is dead now, and it is now that I can finally understand: she was a native of the vibrant, mountainous Lebanese countryside, a place where people built their homes according to their imaginations. They invited you in. You talked and sang and drank coffee and later at night, you drank sweet anise-spiked arak, a vodka that clouded like milk with an eye-dropper’s worth of water. You didn’t need numbers to know where your best friend lived, didn’t need signs to define a street. You didn’t need stories to escape to because you were happy where you were.

Lebanon’s esoteric, mangled paths disintegrate into hillsides. The zigzagging terraces sidestep property lines, run into neighboring public terrain. The steep roadways run muddy in winter and if you are so unlucky to find yourself there, you are at the mercy of whatever village you end up in — all are hospitable, pending your social skill in approaching them. The streets don’t have corners and addresses work in three dimensions: left, right, up.

This made Lebanon as frightening to me as America’s frigid, gridded structure was to Teta. I was — and still am — uneasy in Lebanon. Even as a kid, the country had a wildness that was as palpable as a trapped rabbit’s thumping heart. No matter where you were spending your time, you were aware of the quickness of that rhythm, its simultaneous ease, dependable beat. I despised the ricocheting sunburnt lizards, the rowdy boys who fished jellyfish from the beach and ran after girls with them, the screen-less windows, the sidewalk-less roads, the stench of unfiltered gasoline, the mothers who disciplined their kids and didn’t care who saw. The men who talked as if on stage, smacking backs with palms large enough to crush a cantaloupe. A big-mouthed cousin once poured sand in the novel I’d brought with me to the beach, and asked how Americans could be so dumb if we even spent our vacations reading.

But that unruliness did not faze my grandmother. She couldn’t project written figures on her surroundings, true, but she’d never needed to. The opposite was true for us. If you don’t speak and read English in America, you’re profoundly limited. Literacy facilitates success. Literacy, in our new world era, is luck.

My parents knew this. My mother instilled in us a love for public libraries since our toddler days. She celebrated our scholastic triumphs without pressure or severity. She taught us to read and write Arabic. She’d scold in that cool, unbothered way that forces you to listen: “If you learn, what do I get out of it? It’s all for your self.”

Mama inherited her good looks — along with her insistent belief in God, in luck, in fortunes growing and tides turning — from Teta. Mama lights candles for us during exams. She doesn’t wash clothes on Thursday nights. She sends money to orphanages every year for Eid el-Adha. When I started graduate school, she wrote a classic prayer for me, folded it, sewed it into a tiny piece of cloth, and had me clip it to my bra strap. If I came home sick or angry, she’d ask, “Did you wear it today? See. That’s why.” When she makes dough, she presses her hand into the mound before covering it and allowing it to rise: first, five fingers for our five prophets, then a poke in the middle of the palm for God.

When we were driving to the airport in 2000, I’d forgotten my coloring book (my favorite one, no less) on my bed. I begged my parents to turn the car around so we could get it. My father — a softy, a daddy’s girl dad — made a motion to take the next exit, but my mother stopped him. “Do you want to curse this trip?” she asked us, seriously. My mother is terrified of planes. “It’s bad luck to go back! I will buy her another book!”

So pervasive were these practices in our home that I continued them in my dormitory, in my apartments. If I forgot something dispensable at home, I left it alone. I didn’t leave food on my plate. I asked God’s forgiveness if I dropped bread on the ground. I never put my feet up on the coffee table, where we ate. I turned over flipped shoes so that their heels were not facing heaven. I did this even in the homes of my friends. Once, black-out drunk at a house party, I found myself flipping sandals and flats and heels at the entrance of the fraternity, the practice literally sobering me.

I didn’t notice how much these tiny rituals meant to me until a month ago, right before I took the final section of my clinical licensure exams. I texted Mama to light a candle even before I took my loupes out of their case. On the paper tray, adjacent to my mirror and explorer, I wrote the only Arabic phrase that comes as naturally to my hand as it does to my lips: in the name of God, the compassionate, the merciful. This was a recurrent header on exam booklets throughout undergrad and dental school. If I didn’t do well, I blamed the restrictive Scantron.

No one found out about my rituals. After all, you never want to sound illogical (as a woman). You especially never want to sound illogical in America (as a woman of color). You aren’t supposed to believe in good luck or bad luck, in ghosts, in spirits, in the intangible world. You can’t blame your misfortune on the evil eye, and you can’t attribute your success to God — of course, you do both, but you certainly don’t ever talk about it. The same way you don’t ever decide what apartment you’ll rent when you move to NYC based on the number of the floor (send all queries to 3B).

In ’15, my roommate and I were hoping for a snow day, so we sat in our kitchen and kept refreshing our emails every three seconds. I’d already brewed a pot of coffee and planned to stay and finish it whether we had a snow day or not. I notoriously missed a lot of class.

“We deserve a snow day!” I remember claiming indignantly, as if I was some star student. We’d just endured an intensive week of preparation for our board exams. Optional lectures, and I’d missed them all.

She agreed with me. Unlike me, she was a serious student, but she was unlucky. She did poorly even when she tried hard. I was infuriated on her behalf. I never tried hard but tended to score above average. While we waited, she kept crossing her fingers and sending me fingers-crossed emojis from across the table. We didn’t get a snow day, but most of our professors didn’t show. Our first thought was, of course, that it was such bad luck.

After Teta died, I started to wonder if it was her belief in luck that killed her. I considered the language of luck, how it passed down through her blood and milk to my mother, to me. When I buy exactly three oranges or five kiwis, what am I trying to prevent, exactly? What am I trying to cause? And why do I feel that participating in these small deeds will alter my life in some abstract positive way?

The language of luck is the language of the defeated. Luck is all you have when you don’t have anything left. It’s also what you blame in that situation. The small rituals — the prayers, the bread, the shoes, the dough — are the rules you follow hoping to be rewarded. Yet somehow even the rewards are lucky, meaning you didn’t necessarily earn them. When they’re unlucky, you start wondering what you did wrong so you can take part of the blame. You didn’t clip the prayer to your bra or you threw out a bag of bread.

We hide our rituals in America so that we aren’t judged for what might seem like backwards, third-world vestiges, but the more likely truth is that luck doesn’t measure up in American culture. America blames you for your shortcomings, for your inability to succeed. You don’t get an alibi when things go wrong or a prayer when they might go right. You sign on the dotted line with an unfamiliar hand.

Teta knew she was diabetic in her early 40s, but when she began to experience the paralyzing effects of her disease, she turned to prayer. She asked my uncle to drive her to one of our prophet’s temples in the mountains so she could spend the night. At home, she would tie a white scarf over her thinning hair, open her balcony doors, face the green hill that stands in front of our district, and implore God for luck.

Why? Why rest all her hopes and dreams in what translates — at best — to chance? Is it the culture of not asking for what you want out right, because you might not get it? The culture of humbleness and gratitude, for crediting your earnings to a supernatural source so you don’t seem bigheaded? Or is it Teta’s defense mechanism, her orphan years resurfacing as an adult, in search of some authoritative parent figure that promises to deliver what she lacks? Even if I had answers for Teta, I have no answers for myself. I’ve followed her, continued to converse with the cosmos both before and after she left us.

When I started writing about Teta’s pursuit of luck, I was ashamed. It was as if admitting her beliefs somehow belittled her. This is why I opened with my own foolish fondness of odd numbers, a fixation that — frankly, medically — would be described as a little compulsive. I was so convinced of all the good luck that would come to me in ’17 that, in ’16, I ran against a very popular boy to be president of our student body. I was a dork, but I worked hard, and I wrote a persuasive speech with promises I could keep. By some symbolic stroke of luck, I beat him. I made big plans for ’17. We were finally going to graduate! I was going to write a speech. I was going to make changes in the school, for my class, for the world.

Most of all, I couldn’t wait to visit Teta in Lebanon after commencement and treat her like a queen for a few months. But she died at the start of my final semester. So suddenly, so soon, without saying goodbye. At the wake in our small house in Ohio (the house we grew up in, the only house Teta had visited in the states, the house my family would also sell in ’17), a woman I barely know pressed my face to her chest and rubbed my back. I’d been crying for days, my eyes so red and swollen that I only recognized her by her perfume. She was offering condolences but immediately congratulated me for nearing the end of dental school, a feat no one else in our small Druze community had accomplished yet. I said thanks but didn’t mean it and didn’t care so much. I poured her Turkish coffee, a funeral tradition, and went back to staring at my lap. I would learn later that a man in her family — a cousin or son or brother, a young physician who’d practiced in Detroit — had had a heart attack in the winter of ’12 in front of his car and died. She murmured a phrase that I’d heard Teta repeat a lot, and one that I have been turning over in my head ever since: Luck is all the world is.

A very moving account of love, compassion, and loss.

LikeLike

thank you for reading & commenting mary!

LikeLike

I love how you portray yourself and your family – extremely tender and kind. Oh, in case you’re wondering, it took about four hours for the feeling to come back to my lips and for me not to look like I had a stroke. (after your handiwork) You seemed to do a great job and it didn’t scare me one bit to read how freaking young and inexperienced you are! As long as you loved your Grandma, since I am one, you’re the dentist for me!

LikeLike

I love your how honest and loving and kind your writing is. BTW, I know you are concerned about my numbness. It took four hours for me not to look like I had a stroke. I am not the least bit concerned that you are ridiculously young and inexperienced because you loved your grandma and I am a grandma so you are the dentist for me!

LikeLike

Very touching, congratulations!

LikeLike

This is not just so moving and so beautifully written, but also eye-opening. I really miss my grandmother now!

LikeLike